Statistics show that women remain less represented in political positions and engaged in politics (UN 2023). As the world moves towards achieving gender equality in all spheres of life (UN 2023), why is it that women participate in politics less than their male counterparts and what can we do to fix this issue?

Let’s delve into the issue.

To understand the complexities of gender inequality in political citizenship, we must first define and understand what the term gender refers to. Gender is an economic, social and cultural binary which sorts us into one of two groups, men and women (Phipps 2021). It is socially constructed through bodies, institutions, economic structures, language and behaviour (Phipps 2021). As gender has been historically constructed as a binary, gender roles have eventuated according to this binary. These gender roles assign women to the domestic sphere characterised by traits of passivity, sensitivity and weakness, and deem men bread winners for the family characterised by traits of strength and power (Sawyer 1970).

Over the last century, women have fought long and hard to be granted the same rights as men, and to be seen as equals in society. From gaining suffrage in 1918 in the UK, women have achieved liberation in law. British feminist activist Perez has highlighted that “equality on paper isn’t the same as equality in real life”, and dismal figures regarding the gender breakdown in politics reveal there is still a long way to go (Topping 2018). Whilst women and men have formal equality (equality at law), this does not equate to substantive gender equality.

Where is the problem?

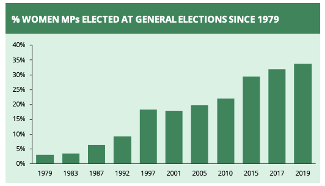

This gender inequality means women remain at a disadvantage when it comes to having their voices heard in the political sphere and contributing to politics. This disadvantage is most clearly seen in the fact that women make up only 34% of the House of Commons (see Figure 1). At an all-time high, this statistic is not representative of the female proportion of the UK population.

Not only are women excluded from decision-making positions, but Fawcett Society figures also reveal that black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) and disabled women are further excluded from these positions (Topping 2018). Whilst BAME women constitute 7% of the UK population, these women make up a mere 4% of MPs, and there are only two women MPs in the Commons who identify as disabled (Topping 2018).

Women from ethnic backgrounds are at a further disadvantage due to intersectionality. Intersectionality refers to the consideration of the multidimensionality of oppression and discrimination, which has traditionally been thought of as only occurring along a single categorical axis (Crenshaw 1989). It acknowledges the importance of the multitude of oppressive forces that place marginalised peoples such as Black women at ‘the intersection’ of multiple avenues of discrimination (Crenshaw 1989; Brah and Pheonix 2004).

Why is this problematic?

For Parliament to be truly representative of all sectors of society, the elected representatives must be diverse. Issues that affect certain ethnic groups, genders or classes are not being effectively addressed whilst they are the hand of white, middle-aged male politicians.

What can we do about it?

A controversial but arguably necessary solution to the problem of the underrepresentation of women in political positions, is to introduce a quota system. Quotas ensure women constitute a certain number of the members of a body, increasing women’s representation (Idea International 2023). Studies show that quotas are imperative to addressing the massive imbalance of power in Britain (Topping 2018). Sam Smethers, Chief Executive of Fawcett Society states that “Equality won’t happen on its own. We have to make it happen”.

Figure 3 explains what gender quotas are, and where they have been effective.

Figure 3: Institute for Gender and the Economy Video (2018).

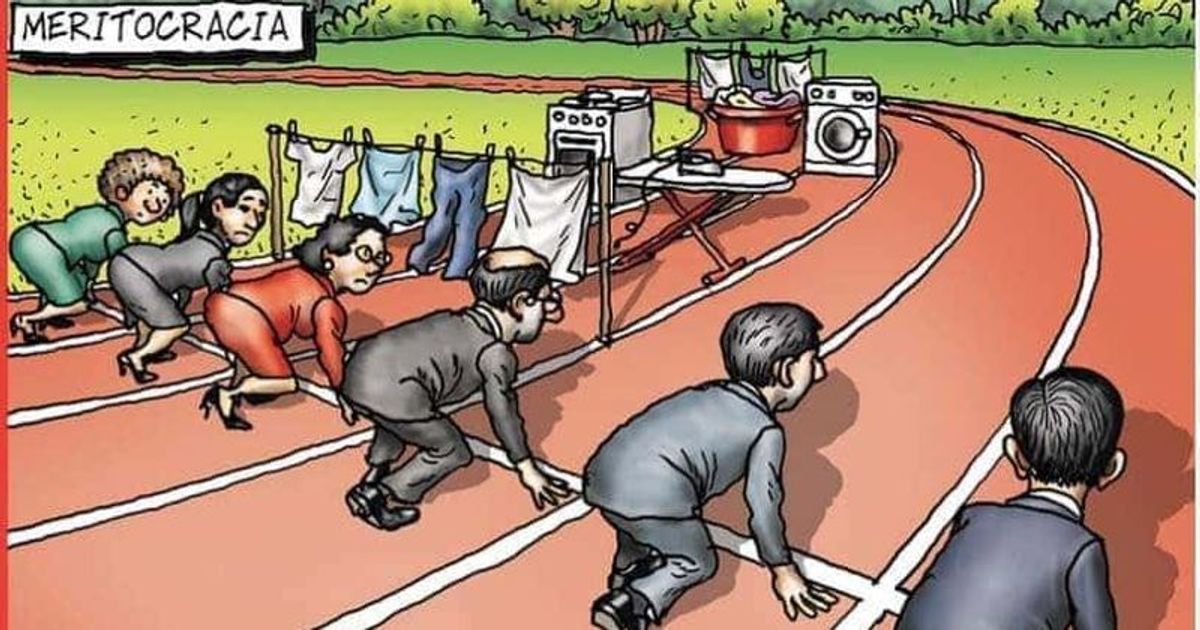

Quotas aim to address the systemic issues that result in gender inequality in politics (see Figure 4), and fast-forward the process of achieving equal representation.

However, quotas are often deemed controversial. The argument against gender quotas is that quotas recruit representatives on the basis of their gender, rather than their merit, and so are by definition unmeritocratic (Murray 2015). However, Murray (2015) argues that recruitment without gender quotas is unmeritocratic, because the recruitment process is inherently based on (male) gender privilege, and starts on an uneven playing field. Further, definitions of said merit, of which the recruitment process is arguably supposed to be based off, are synonymous with education, income and prior political experience – measures that are usually markers of social privilege (Murray 2015). The merit vs equality argument regarding gender quotas then rests on the assumption that underrepresented groups in politics including women and ethnic minorities, are in fact absent from politics because they don’t deserve to be there (Murray 2015). This is untrue. We need a diverse and democratic parliament to ensure that all segments of society have their voices heard and their issues represented.

Another solution to the gender imbalance in politics, suggested by the Fawcett Society, is to urge the government to enact s 106 of the Equality Act, which requires political parties to report the diversity of their candidates (Topping 2018). Despite the law no data is collected and there is no monitoring of party representation regarding disability, ethnicity or gender.

What do you think is the best solution?

Bibliography:

Brah, A, Pheonix, A, 2004, ‘Ain’t I a Woman? Revisiting Intersectionality’ Journal of International Women’s Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, 75-86.

Crenshaw, K 1989, ‘Demarginalising the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics’, The University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 139-168.

Idea International, 2023, ‘Gender Quotas Database’. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/gender-quotas/quotas#what [Accessed 20 March 2023].

Institute for Gender and the Economy, 2018, ‘The Brief: Do Gender Quotas Work? [ONLINE VIDEO] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRDuZ7xVFDs [Accessed 23 March 2023].

Murray, R, 2015, ‘Merit vs Equality? The Argument that Gender Quotas violate Meritocracy is based on Fallacies’, London School of Economics. [ONLINE] Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/merit-vs-equality-argument/ [Accessed 14 March 2023].

Phipps, A, 2021, ‘Feminism 101: (De)constructing gender’, Prezi. [ONLINE] Available at: https://prezi.com/_ikpopec–ac/feminism-101-deconstructing-gender/. [Accessed 20 March 2023].

Sawyer, J 1970, ‘On Male Liberation’, Liberation, vol. 15, no. 6, 7 & 8.

Topping, A, 23 April 2018, ‘Britain needs gender equality quotas now, Fawcett Society says’ Guardian, [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/apr/23/gender-equality-quotas-fawcett-society-britain [Accessed 14 March 2023].

Uberoi, E et. Al, 2020, ‘Women in Parliament and Government’, House of Commons Briefing Paper, 25 February 2020.

United Nations, 2023, ‘UN Sustainable Development Goals’. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ [Accessed 14 March 2023].