The story of Athena and Arachne leaves a message that carries meaning over time and place. Originally spun as part of book VI in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, it speaks of the downfalls of human pride and cleverness.

Ovid was a poet who, in 8 CE, finished his most epic narrative: Metamorphoses. It is still one of the greatest compilations of beloved Roman mythology to date, and in fifteen books Ovid emphasizes some of the most common themes in classic Greek and Roman mythology. Although the tale of Arachne is short in comparison to some of the others in Metamorphoses, it depicts some of the most influential motifs in mythology. I specifically chose to write about this story because I believe that, even in today’s society, we can learn from the lessons told in mythological and religious literature. We could benefit from paying heed to the consequences of things such as pride, disrespect, and the desire to test fate. If only Arachne had this foresight, her fate may not have been sealed as dimly as it was.

Arachne was a woman of humble upbringing and an artist whose only recognition came from her work. Therefore, it seems reasonable that she shows great pride in her skill. As in many cases though, there is a line between pride and arrogance. Arachne crosses this boundary when she contests the great craftswoman goddess Athena. Unlike Ovid himself, who asked for the gods’ blessings to write his prose, Arachne does not respect the authority and humility of her religion and stubbornly challenges the goddess to a weaving competition.

Gods and goddesses do not take kindly to the idea of mortal beings coming anywhere close to perfection. Athena reacted with swift vengeance when Arachne’s weaving was shown to be a stunning, yet disturbing depiction of the numerous crimes of her fellow gods. Arachne had shunned the religious attitudes of her people; some of which included gratitude to the Olympians and an acceptance of mortals lesser role in life and their imperfections. She had upset the balance of nature and a reckoning, as per usual in mythology, was necessary. Thus Arachne realized too late that she had disrespected the wrong person and in her shame she tried to kill herself. Athena showed more mercy than normal by turning Arachne into a spider and allowing her to live.

This tale is sometimes said to be a creation story and the origin story of arachnids. I do not disagree, but because of its intricacy and its plot, this text has subtle lessons and warnings that are meant to mold mankind into cautious and subservient believers. Just like the Bible is to Christians, the ancient Greeks and Romans lived and breathed the stories that represented their past so that they could lead a devote present. Gods and goddesses were simultaneously loved and feared and were no more fiction that the air and the earth. Although I cannot see the story of Arachne and Athena from these peoples’ perspective, there are a few details that stand out above the rest.

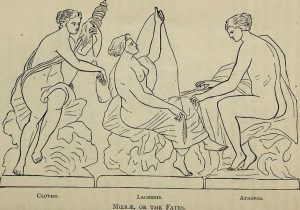

At the beginning of the tale, Athena approached Arachne and gave her the opportunity to give credit to higher powers for her talent. This does not fit the short-tempered and punishing profile established in my mind. It shows that fate is grey. We sometimes have the ability to adjust our own future and fix mistakes that could lead us down the wrong path. It is a glimmer of hope to see the story from this mindset. Also, in the same line of thought, and contradictory to what I just wrote, it seems a little ironic that the opportunity to change fate even exists at all. I remember from reading myths growing up that there are three “Fates”: crones who weave a tapestry of their own which affixes each and every individuals inevitable lot in life. I think the conflict of the Arachne’s opportunity to change her fate and the Grecian idea that fate is sealed from the beginning is what drew me to this story. Myth can be interpreted in so many ways; it is only each reader’s interpretation that, in the end, counts.

My personal interpretation is even applicable to today. Morals and lessons never lose value; they just alter to fit the times. There are so many conflicts going on in our world that we have the ability to grasp, find a solution to, and change before it is too late. I have known this story for a long time, ever since my mom read abbreviated myths to me when I was a kid and more in depth in college. Each time I read it there is something new and tangible in the world that its lessons can be applied to. This class was a good way for me to remember that behind every seemingly ridiculous story is a bigger picture.

Bibliography

Anon, Arachne. Greek Mythology. Available at: https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Mortals/Arachne/arachne.html [Accessed June 30, 2017].

Gill, N.S., Who Won the Weaving Contest Between Athena and Arachne? ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/weaving-contest-between-athena-and-arachne-117186 [Accessed June 30, 2017].

O. & Miller, F.J., 1966. Ovid Metamorphoses: with an English translation, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

is a good or a bad guy a little bit more complicated. Even though he wasn’t in his right mind, someone has to take the blame and I think that it still lands on his shoulders.

is a good or a bad guy a little bit more complicated. Even though he wasn’t in his right mind, someone has to take the blame and I think that it still lands on his shoulders.