The Legacy of the Plough

Eighteen years into the 21st century, it should go without saying that men, women and non binary individuals, while different, are equal.

After all, are we not all human beings?

To understand how gender inequality came into being in the industrialised and developed world, we can look to the history of human development to shed some light on the origin of gender specific roles in society.

What we find, in a paper written by Alesina, Guiliano and Nunn entitled ‘Women and the plough: On the organs of gender roles, produced for the National bureau of Economic Research (Alesina, Guilano & Nunn, 2011: 469 – 530) tests the hypothesis that,

“traditional agricultural practices influenced the gender division of labour and the evolution and persistence of gender norms”.

Their finding is that descendants of societies that traditionally practiced plough agriculture now have lower rates of email participation in politics, entrepreneurship activities and the workplace, than in societies without that inheritance.

This is consistent with the fact that most developing African counties have a greater degree of female MPs in their government than many of their developed, first world, European counterparts according to the House of commons library 2018, ‘Women in Parliament and Government and Briefing paper, SN012050, (House of Commons Library, 2018)

I was staggered to discover that the ‘mother of parliaments’, Westminster, had a lower female rate of participation than Mozambique, Namibia, Ethiopia or Rwanda, the latter leading the table with 61% of it’s MPs being female.

These figures would seem to support the ‘Women of the Plough’ theory above.

While it is generally accepted that women in our society no longer define themselves as potential or actual ‘mothers’, accepting a traditional role to bring up children, at the moment at least the biological role of women which is imperative for the survival of the species, it being women who are capable of carrying a foetus in utero, to give birth and then to nourish a child from birth; this role is undeniable.

This clear biological difference and imperative may suggest that gender difference in the economic role played by women is essential, while one parent, the one not fulfilling the role of birth giver, works to support the mother, although this view has been increasingly unpopular since the advent of second wave feminism, particularly among middle class women with potential for career development and higher earnings.

However, I personally find the ancient traditional role of ‘Women of the plough’ unsettling in itself, the image of pregnant women behind a plough and subsequently manually grinding corn for hours on end would cause me to take over the heavy duty agricultural work while the pregnant women put their feet up and enjoy a cup of tea and a nap.

The change in attitude in our first world, post industrial, post modern society with it’s enlightened feminism is, however, threatening the very values it is based upon, as Europe in particular is now failing to be sustainable, with tremendous fall in birth rate.

According to William Reville, Professor Emeritus at UCC, writing for the Irish Times, May 16th 2016 in his article, Why is Europe losing the will to breed’,

“European civilisation is dying. It is dying in plain sight and almost nobody is talking about it” (Irish Times, 2018)

He goes on, “Birth rate in all 28 EU countries are now below replacement rates and all indigenous populations are in decline”……………and to become sustainable…”it is necessary for each woman to give birth to 2.1 children”, whereas at present the EU average now is 1.56.

(Rand Corporation, 2005)

Reville goes on to suggest that,

“Part of the reason for this is the change in the social role of women, many of whom are now in the mainstream workforce and as committed to career development as men. Many women delay having children until later in life and career pressures limit the number of children per family”

Reville also goes on to point out the internal assault, as he puts it, of post modern intellectual elites, who, “embrace moral and cultural relativism, multiculturalism and political correctness, attack our values and weaken our will”.

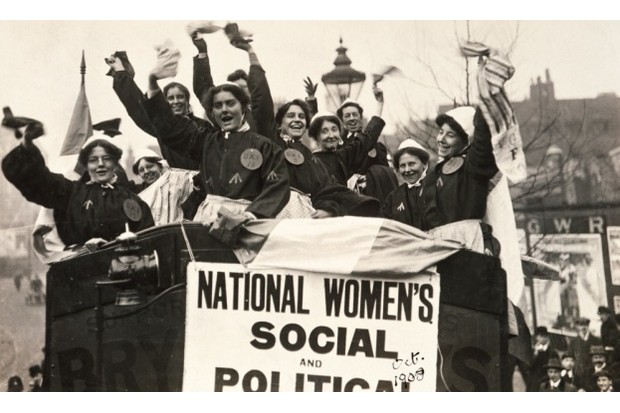

Change in political engagement since 1918 has become defined by gender, whereas it has broadened the political platform not just for women, but also for working class men, whereas prior to 1918, it was solely the preserve of property owning, therefore middle class men and the upper class elites.

Improvement in earning power and opportunity in the work place has almost entirely been to the advantage of middle class women, rather than to women overall, hence the ‘gender pay gap’, whereby equal pay fails to address the gender pay gap for working class women. Middle class women, due to the often ‘non manual’ nature of their career choices, can more easily and realistically aspire to equal pay with male colleagues, as a teacher, lawyer, medic or in the upper ranks of the corporate world, once a glass ceiling is removed.

(Lethaby, 2018)

However, the roles for working class women and men remain more separate and easily defined, and less easy or realistically to quantify with equanimity, hence many traditionally ‘female roles’ such as in retail and care, remunerating far less well than traditional male roles such as haulage and construction.

The role of all women, in particular working class women, in advancing the role of women in political engagement, has, since the First World War, been driven by the necessary involvement of women at times of crisis, whereby women have been able, as a result to demonstrate their ability to do the same work as men, in whatever sphere of work.

The election of the greatest number of female MPs in history, in one go, was achieved in 1997, with the introduction of what became known as ‘Blair’s babes’, at once undermining the equality of women just with the use of the diminutive language used.

According to Rachel Cooke, writing for the Guardian, 22 April 2007 in her article, ‘Oh babe, just look at us now!’ (Guardian, 2007) a reflection on the experiences of those women ten years on from their election, Cooke discusses the contradictions and difficulties they faced, as many of them mothers, became somewhat overwhelmed by the difficulties of reconciling their ground breaking political careers with the need and wish to be good and present mothers.

Notwithstanding these difficulties however, the number of female MPs, which is a signal of gender political engagement, rose to 208 by the election of 2017, and while still lagging behind Rwanda, from a gender equality point of view, this is surely a firm stride in the right direction.

Bibliography:

Alesina, Guilano and Nunn (2011) “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough”, in the National Bureau of Economic Research, 128 (2) 469 – 530

Cooke (2011) Oh babe, just look at us now, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2007/apr/22/women.labour1, (Accessed: 19/4/2018)

House of Commons Library (2018) Women in Parliament and Government, Available at: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN01250, (Accessed: 19/4/2018)

Irish Times (2016) Why is Europe losing the will to breed, Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/why-is-europe-losing-the-will-to-breed-1.2644169, (Accessed: 19/4/2018)

Lethaby (2018) Suffragettes and Working Class Men 100 Years Ago!, Available at: http://www.boblethaby.co.uk/2018/02/suffragettes-and-working-class-men-100-years-ago/, (Accessed: 19/4/2018)

Rand Corporation (2005) Population Implosion, Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9126/index1.html, (Accessed: 19/4/2018)