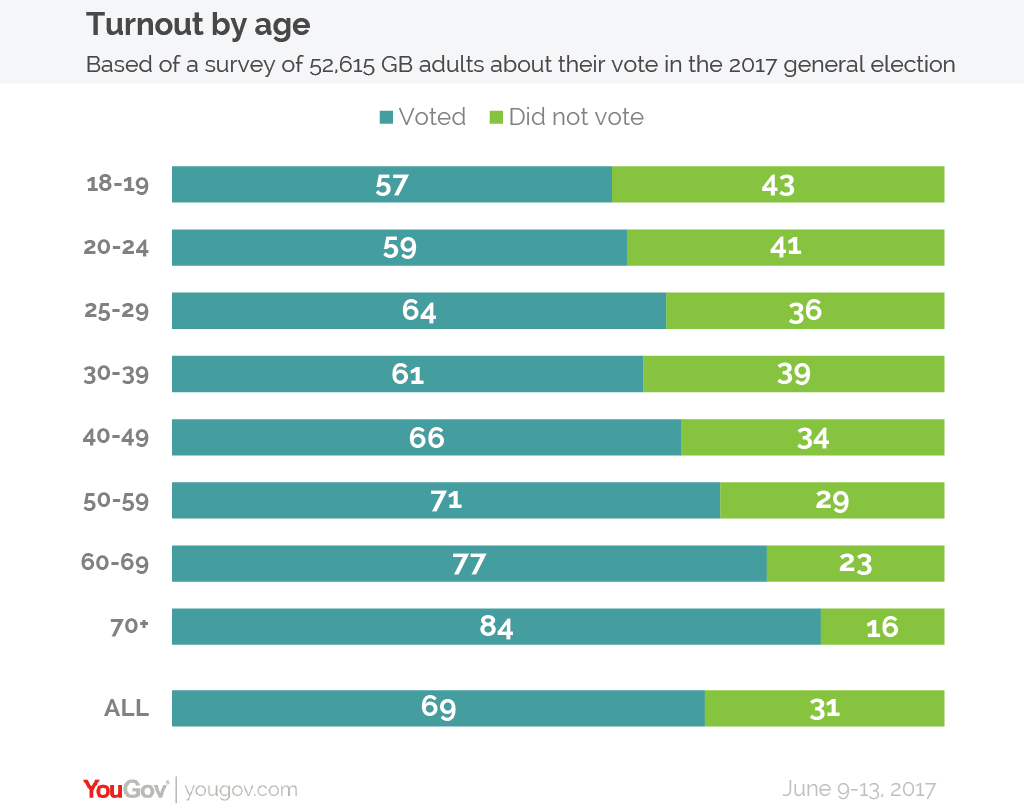

For so long, young people in the UK have felt as though politics is not for them, doesn’t concern them nor did it interest them. However things are starting to change. The older age groups of British society have enjoyed a monopoly on politics with policies that benefit them to the detriment of the younger populace leading some to call the UK a gerontocracy. Before the EU referendum and the General Election in 2017, youth turnout in voting was relatively poor. For example, the 2019 general election saw a 47% turnout of young voters, a decrease in 7% from the 2017 GE, but perhaps even worse there was a higher turnout amongst older voters aged 45 and older (Mashford,2020). This imbalance in age demographics and their political engagement thus means that the age-group underrepresented at the polls are far more likely to have policies that put in place by governments that reflect their interests, remaining underrepresented. The graph below shows a YouGov survey of voters based on age how they voted in 2017.

So why the decrease in youth turnout between 2017 and 2019?

A lot has been made of the supposed ‘youth quake’ in 2017 with records of numbers of first time voters showing up to the polling station – to vote for Jeremy Corbyn. but to put it simply, Corbyn ran a great campaign aimed at young voters with policies with their interests at heart. (Prosser et al , 2018) These included the abolishing of student debt and minimum wage of £10 per hour.

So how valuable is representation at the polling stations?

The UK, like most other developed countries has an ageing population due to higher life expectancy resulting from good healthcare and lower birth rates from more young people prioritising their careers over having children. This thus means the older age groups are more likely to head to the polling stations, which incentivises policy makers to centre their potential policies around the most represented groups of voters to increase their chances of getting into office and/or staying there. However this all occurs at the expense of younger voters, who remain in the periphery of many policy makers and thus have their own interests shelved. So how can we change this if at all?

Using data from the Office for National Statistics we can see that the UK is likely to stay as ageing society for the foreseeable future. This graph shows the percentage of which those aged 65+ have made up of society, comparing 1971 to 2017. the dotted lines indicate the predicted trajectory of the make up of this age group. The proportion of the adult population over 65 has increased from 18.5% in 1971 to 23.2% in 2017. Meanwhile, the proportion of those over 55 has increased from 34.9% to 38%. Over 55s are projected to constitute 46.2% of the population in 2050, and over 65s, 37.1%.

As mentioned before, the most represented groups at the polling stations are likely to have polices put forward in their interest by policy makers to ensure they stay in power. however there is slight cause and causation conundrum where its unclear that the disengagement of young people in politics actually hinders their cause on the political scene and thus their interest aren’t taken up as much by policy makers, or its that because of the shelving of the interests of young people’s political interests they have become disengaged with politics,

So what are potential solutions to youth disengagement?

social media has become such a powerful tool in recent years regarding news and the spread of it. it has taken away the monopoly the traditional forms news (TV, newspapers, radio etc) had enjoyed over the news agenda over many decades. the rise of citizen journalism in the midst of chaos has created massive change in politics and legislation. for example, in the US when George Floyd was brutally murdered by a police officer, not only did it cause outrage across the Atlantic and around the world, it also led to the prosecution of police officer accused of murder for the first time in US history. The video of the murder was recorded and published by a 17 year old girl on social media. The aftermath of George Floyd’s murder saw many conversations regarding police brutality and institutional racism in the UK take place with cases of police brutality in the Met Police being brought to light. many of these discussion took place on social media and thus by young people. When Whitehall was filled with protesters demanding change in the summer of 2020, the vast majority were not of the age group most represented at the polling stations. these protest were organised online, namely on Twitter. but the conversation were not restricted to the internet only. eventually traditional media mediums caught on and invited some of the voice behind the twitter accounts and megaphones on TV. for example during the protests at Whitehall, Winston Churchill’s statue was defaced, causing widespread outrage mostly amongst older generation who regard him as a true hero and the greatest Briton to ever live. the came in contrast to the views of younger people who saw him for the raging racist and genocidal maniac he was citing the famine he cause in the Bay of Bengal. as well as his great disdain for the formation of the beloved NHS which he opposed the formation of 22 (twenty-two) times. However despite this, there was still string resistance on the other side to uphold him as some sort of hero.

In this video Scottish MP, Ross Greer reflect those conversation had on social media on TV, much to the dismay of one Piers Morgan. what can be seen as symbolic is that Ross Greer, a young MP’s views clashing with that of the older Piers Morgan and both these points of views were given platforms on social or TV and other traditional media outlets. this heightens the age divide in the UK that also comes with cultural divide. With many older people nostalgic off post war Britain whereas it seems for younger Briton’s its a Britain they don’t recognise and/or identify with.

Essentially what can taken as a massive plus from this is that as the impact and influence of social media grows, those who use it most will be heard, through mobilisation and demanding that they are heard and of course actually heading to the polling stations. But arguably more importantly, the myth of youth apathy with regards to politics is finally being found out.

Bibliography:

Prosser, C. Fieldhouse, E. A., Green, J., Mellon, J., and Evans, G. (2018) Tremors But No Youthquake: Measuring Changes in the Age and Turnout Gradients at the 2015 and 2017 British General Elections.

Chrisp, J. and Pearce, N., 2019. The rise of the grey vote. [online] IPR blog. Available at: <https://blogs.bath.ac.uk/iprblog/2019/05/21/the-rise-of-the-grey-vote/>

Mashford, S., 2020. Youth turnout – How does the UK compare to other European nations?. [online] 89 Initiative | The first European think-do tank. Available at: <https://89initiative.com/youth-turnout-uk-europe/>