“Society can survive only if there exists among its members a sufficient degree of homogeneity; education perpetuates and reinforces this homogeneity by fixing in the child, from the beginning, the essential similarities that collective life demands. But on the other hand, without a certain diversity all co-operation would be impossible; education assures the persistence of this necessary diversity by being itself diversified and specialized.”

Durkheim (1922)

Young people and their political engagement appear essential for generating a collective society based on everyone contributing to the greater good, but this is not always the case within the UK. I will argue that part of the problem is the ‘division of labour’ previously explored by Durkheim (1895): where work is increasingly specialised ensuring society has become fragmented as a result. All of this arises within the classroom environment.

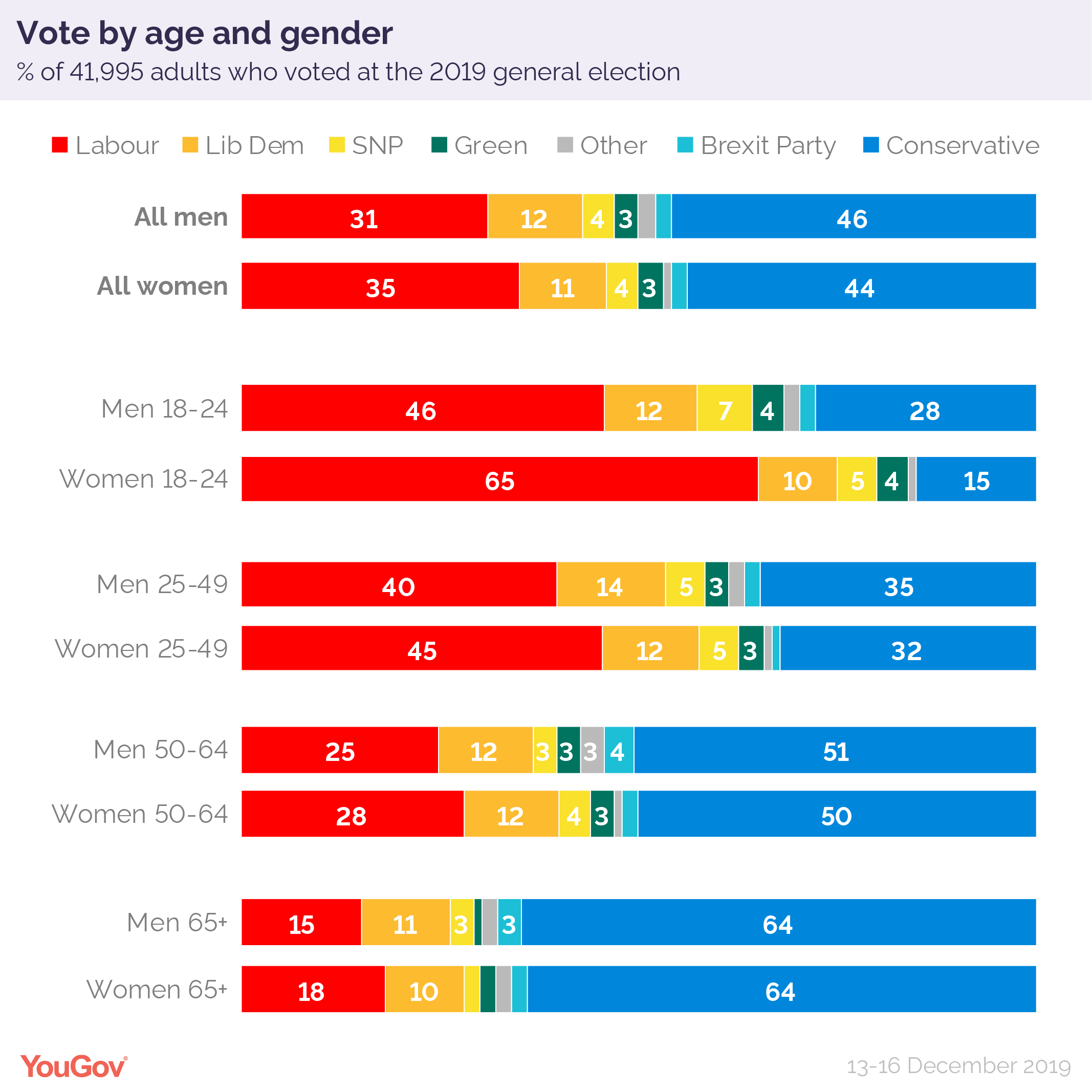

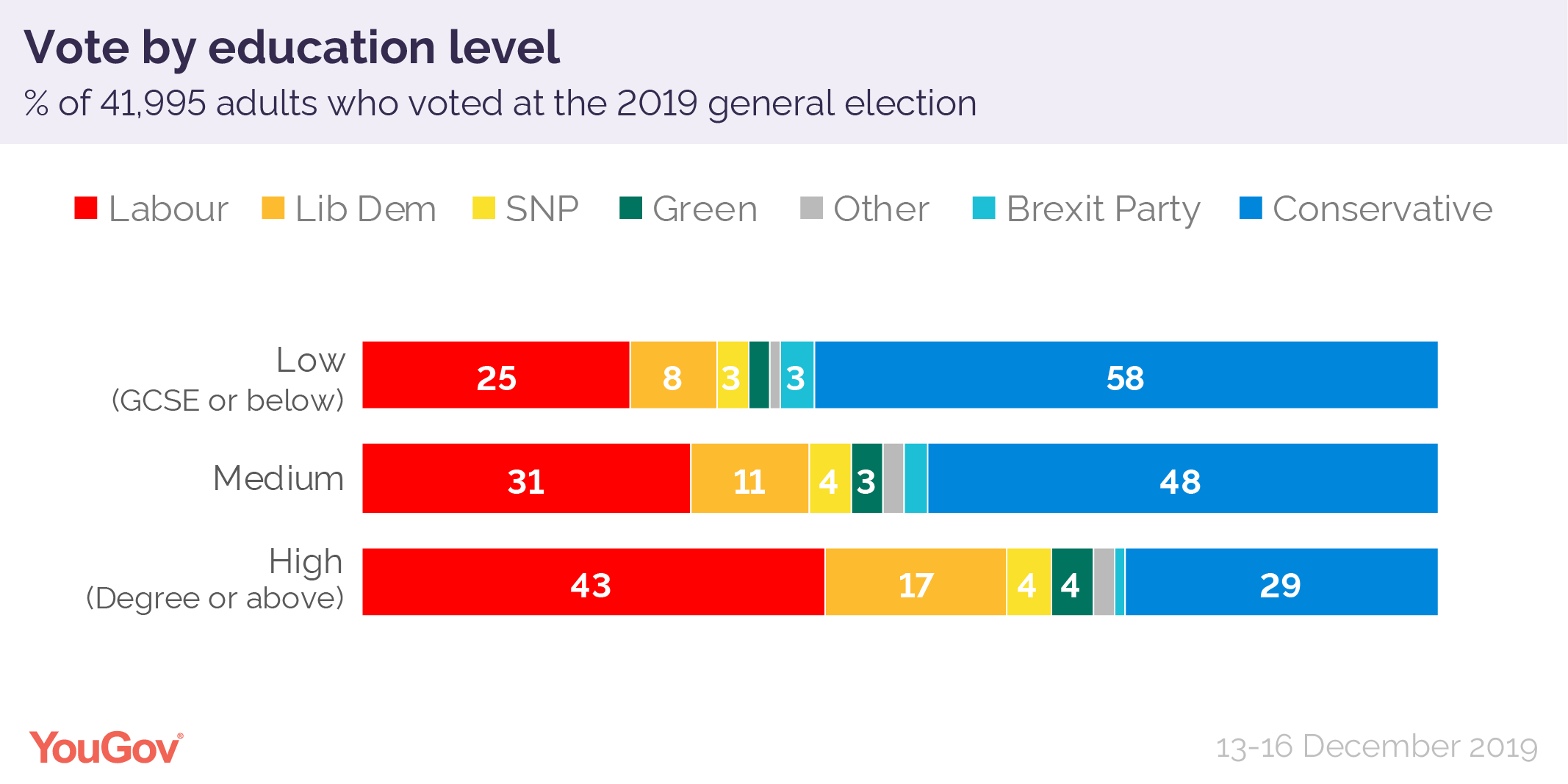

Previously, Keating and Melis (2017) argued that young people are not a homogenous group, and clearly, from my experience some young people are more politically engaged than others. For me, understanding this dynamic, by drawing on Willis (1977), this becomes central to thinking about a division arising at school between the ‘lads’ and ‘the earoles’, echoing my previous school experience. This division later becomes pronounced in voting patterns and was confirmed by YouGov (2019). Now the problem has been defined we need to think about remedies before our society falls apart.

Whilst young people are often viewed are termed ‘millennials or some other totalising term, there are ruptures and cleavages within us (Keating & Melis, 2017). A split has arisen between those young people who have an investment in the current social arrangements, broadly known as the ‘socially included’ and those increasingly isolated, labelled as the ‘socially excluded’.

In thinking about these differences, Janmaat & Hoskins, (2021) drew from the Youth Survey of the British Household Panel Study along with Understanding Society to explore how this split occurred. At the age 11 as we all emerged from our primary to enter into secondary school there were minimal differences between us in our levels of political engagement. However, something happened to us between 11 to 15 where our interest in the wider world began to wane. Furthermore, it appears there is a marked split between those families who had cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984) such as having access to books and engaging in family discussions whilst others lived in families where no one spoke about politics and there were no books. The following table (1) shows the split:

Table 1

In Table 1, parental educational level, or levels of cultural capital (Hoskins & Janmaat, 2019) ideally propels their sons and daughters into further learning. In contrast, those from less educated families disengage from mainstream society, seemingly because there is limited support.

In thinking about how these dynamics operate on the ground the key theorist is Paul Willis (1977), a researcher who hung out with a group of ‘lads’ in a Midlands Secondary School. He watched as the young men disrupted the school system, physically attacking the ‘earoles’ as they bragged about smoking, drinking and having girlfriends whilst displaying cynicism and apathy, all at the age of 13/14. As a young person reflecting back onto former school days, who has not come across this?

The lads were spellbound by the world operating beyond school and were entranced by displaying alleged masculine values such as physicality and entrepreneurship whilst laughing at anything seen as ‘soft’ such as school learning. Alienation from the school led to a gender gap around political engagement. Willis’s (1977) study shows how young men, and some young women transform their attitudes towards the school as they resent and disrupt it, until they are excluded, firstly from education and then from wider society.

Table 2

Table 3

For me a picture emerges where those who were disengaged from school later voted for political parties which promise to redress their alienation and marginalisation with empty promises based on redress. It appears that the power elites (Wright-Mills, 1956) have harnessed sections of the marginalised to build their power blocks in order to further their own interests. The marginalised never saw this coming and as a result society is in danger of fracturing (Durkheim, 1922).

Remedies

In response to this fragmentation amongst young people, three solutions are proposed: citizenship education, ensuring the marginalised voices are represented and all of us engaging with social media. Hoskins and Janmaat (2019) stated that solidarity and insight can be developed through the promotion of active citizenship classes such as those currently run in England’s Secondary Schools. The important role of Citizenship Classes was previously investigated by Pontes et al (2021) as (n=1025) young people; aged over 18 in 2010 took part in an online survey. This provided a comparison between those young people who took active citizenship classes in England versus other groups of young people from Scotland, Wales and N Ireland who did not attend these classes. The results revealed that attending the citizenship classes ensured the students had a greater understanding of the various political intricacies and engaged with political ideas resonating with Hoskins and Janamaat’s (2019) position.

Another dynamic as noted by Cornwall (2016) requires young people to be actively engaged in politics because: “participation is ultimately about power” which has meant shifting from expert-led top-down modes of governance to: “challenging and changing deep-seated cultures of politics and bureaucracy” (Cornwall, 2016). As young people we need to have our voices heard and challenge the status quo.

Thirdly, Keating and Melis (2017) undertook a survey of young people aged 22-29. They found that the main driver of online political engagement was being able to express their ideas on social media. Whilst young people are closed down everywhere else, social media: Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, WhatsApp, and other sites allow everyone to express and connect, the next step is ensure the rest of the adult world begins to listen.

References

Bourdieu P. (1984) Distinction, Abingdon Oxon: Routledge

Cornwall, A. (2016). Citizen Voice and Action. GSDRC Professional Development Reading Pack no.36. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham.

Durkheim, E. (1895) The Division of Labour in Society, London: Bloomsbury (republished 2013).

Durkheim, E. (1922) The Sociology of Education, https://www.raggeduniversity.co.uk/2014/08/13/sociology-education-durkheimian-view/ Accessed 15th February 2022

Janmaat and Hoskins B (2021) When does the social gap in political engagement emerge in life and can citizenship education address it? https://www.teachingcitizenship.org.uk/blog/08112021-1336/when-does-social-gap-political-engagement-emerge-life-and-can-citizenship, Accessed 18th February 2022

Janmaat and Hoskins B (2021) The Changing Impact of Family Background on Political Engagement During Adolescence and Early Adulthood, Social Forces, 2021; soab112, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soab112

Keating, A., & Melis, G. (2017). Social media and youth political engagement: Preaching to the converted or providing a new voice for youth? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(4), 877–894. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117718461

Pontes, A. I., Henn, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Youth political (dis)engagement and the need for citizenship education: Encouraging young people’s civic and political participation through the curriculum. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 14(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197917734542

Willis P (1977) Learning to Labour: How Working-Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs, London: Ashgate (republished 2000).

Wright Mills C. (1956) The Power Elite, Oxford; OUP (republished, 2000)

YouGov (2019) How Britain Voted in the 2019 Election, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/12/17/how-britain-voted-2019-general-election Accessed 18th February, 2022

Hi Hristina, I think your blog on young people and political engagement was very well written. I particularly enjoyed learning about the impact that parents education and school involvement such as citizenship lessons has on youths involvement in politics. I was also interested to learn about the impact that populist parties have on the wider public. I enjoyed seeing your explanation of how citizenship lessons can help children understand the impact of positive political engagement.

It would be interesting to see more physical evidence to see the actual impact of CPSE and citizenship lessons and learn if there are more tools that could be used to help involve students engage that they would find interesting. Do you think it would be wise for students to have political engaging activities, such as; class trips to parliament house to watch on going debates and learn so they are able to engage better? Would you also think if school council elections were held in the same order and manner as the general elections it could help for them to learn and understand further?

You speak about the impact that paternalist elites have on imposing their ideologies do you think that because we are part of a society in which we are more aware of the impact of ideologies and so we aren’t as impacted by such elites as we now have access to information that wasn’t previously?

Thanks,

Arifa