In this post, I will be discussing women’s political engagement over the past 100 years; how they have gone from not having voting rights at all, to growing into a key component in the political sphere as well as highlighting the space we have to do more in order to .And how little progress has been made in this period How underrepresented women are 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of women over the age of 30, with certain property qualifications being given the right to vote.

There once was a time in the UK where politics was solely a male only game; however, in 1866 a

petition calling for votes for women had managed to accumulate 1499 votes, including the likes of Florence Nightingale, was submitted to Parliament. Even though the petition failed in Parliament, it initiated grassroot women’s movements such as the National Union if Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), which was founded in 1897. The NUWSS continued to strive for women’s voting rights through petitions, marches and peaceful means, gaining 50,000 members by 1914. Despite this, there were many women who had become disillusioned with the lack of progress since 1866, leading to the creation of The Women’s Social and Political Union by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst who adopted a wide range of militant tactics to have their voices heard.

Since women were given the right to vote, the percentage of female MPs elected at general elections has steadily increased. The 2017 elections proved to be a landmark year in British politics as we finally managed to pass the minimum proportion of women representatives necessary for a legislature to be representative of women which is 30%.

However, this ‘achievement’ is nothing but a small victory especially when considering that there are many less socioeconomically developed countries where women are more involved in the political sphere, such as Rwanda and Bolivia as highlighted in Fig. 2.

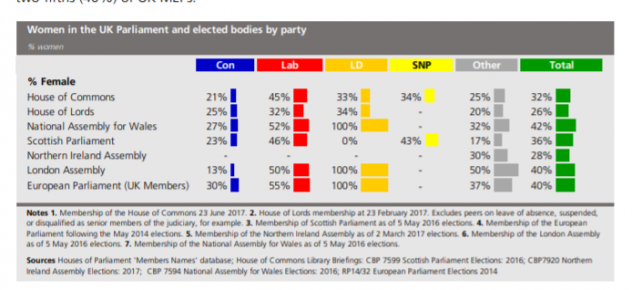

In the UK, women account for almost half of the population (Political Studies Association, 2015), yet, they make up only about a third of members in the House of Parliament. Fig. 3 shows the percentage of women in the UK parliament and elected bodies of the main political parties in the UK; Labour has the largest number of female MPs, with 45% of their House of Commons seats being held by women; this number goes down to 33% for the Lib Dems and 21% for the Conservatives (House of Commons Library, 2018).

What does this mean? It means that women are not being represented proportionately to the electorate in the Houses of Parliament and despite the effortless work and suffering of suffragettes and progress 100 years in, women are being neglected from the political sphere. But why is this? One explanation is that women face disadvantages through a variety of social obstacles; lifestyle constrains such as childcare and the undertaking of domestic work (Shruti et al, 2014) as well as the fact that women are less likely to be in occupations that support political activism (UCL, 2012), for example, women in the UK are most likely to be employed in administrative or carer jobs (ONS, 2017). Komath (2014) argued that women’s lack of representation in the political sphere is deep-rooted in the stigmas and attitudes surrounding patriarchy. Women are often portrayed as weak entities who are only capable of dealing with trivial matters, constantly engaged in gossip and overall less intelligent than male counterparts.

How can we fix this problem of the lack of female representation in politics? Political parties have introduced all women short lists for elections, helping women enter politics (Kelly & White, 2016)

To summarise, the plight of women in the British political sphere has progressed and improved a great deal over the past 100 years; however, there is still a long way to go and plenty of action that needs to be taken if we are to ever have a system that is representative of both men and women. Public attitudes and perceptions of women need to evolve and governmental policies need to be implemented to ensure that women are given the same opportunities as men.

References:

Kelly, R., White, I. (2016). All Women Shortlists. House of Commons Library. 5057. Available: http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN05057#fullreport. [Date accessed 4th April 2018]

Komath, A (2014) The Patriarchal Barrier to Women in Politics. Available from: http://iknowpolitics.org/en/knowledge-library/opinion-pieces/patriarchal-barrier-women-politics [Date Accessed: 10/4/2018]

Parliament.uk (2018) International Womens Day 2018 – Women in Parliament and Politics. Available from: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-8245

Political Studies Association. (2015). Why Aren’t There More Women in British Politics? Available from: https://www.psa.ac.uk/insight-plus/why-arent-there-more-women-british-politics. [Date accessed 6/4/2018]

Shruti, J., Kent, G., DeCastro, R., Stewart, A., Ubel, P., Jagsi, R (2014). Gender Differences in Time Spent on Parenting and Domestic Responsibilities by High-Achieving Young Physician-Researchers. Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (5), 344-354.

UCL (2012) Women’s political participation in the UK Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/political-science/publications/unit-publications/89.pdf [Date Accessed: 12/04/2018]