Your socioeconomic status is confirmed by your place in society and this is defined by the kind of job that you work and the earnings that you make. Where you fall upon the social hierarchy is primarily affected by these two things. “Political participation has proved to be consistently and highly associated with individuals’ socioeconomic background variables, such as income, social status, and education.” (Castillo, et al. 2015)

Education has been the first solid argument that supports the theory that the higher your socioeconomic status is the more likely you are to participate in politics. This is because your “level of education (or educational attainment) has been consistently presented as one of the most important determinants of political engagement,” as you will not have the means to participate in a political matter without the required knowledge. Education does not only provide an individual with knowledge in politics, but it also allows them to gain an interest in the political world in order to participate and contribute their votes to see the policies that they agree with come into play.

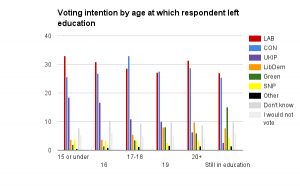

Source from: Alfonso, A. (2015). To explain voting intentions, income is more important for the conservatives than for labour. Access at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/to-explain-voting-intentions-income-is-more-important-for-the-conservatives-than-for-labour/

If we take a look at the graph above, we can see that the number of people who decided not to vote and left education at the age of 15 or younger is higher than the amount of people who decided not to vote and left education at the age of 20 and above. This somewhat supports the idea that education is a key factor that effects the political participation of the individual. The reason why I say that it somewhat supports this claim is because the socioeconomic status of an individual potentially promotes social exclusion. Being forced into a group of social hierarchy discourages those at the bottom of the hierarchy from voting, especially when political ideologies tend to be against their favour. Hoskins and Janmaat’s (2016) argument reinforces the idea of social exclusion as “disparities in political engagement are said to lead to public policy that favours the elite and enhances social exclusion.” At this moment, “the world of politics is culturally closer to middle-class experience, and arguably increasingly so, while individuals socialized in the working-class culture are alienated from it,” (Lahtinen, et al. 2019) and are therefore less likely to engage in a democracy in which they feel excluded from.

The labour party in the recent election was able to increase participation by creating a manifesto that appealed to the working class. They won themselves a large number of seats in urban areas because their manifesto was focused on meeting the needs of those who are perceived to be at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. The high number of voters who came from low socioeconomic backgrounds disproves the theory that individuals who belong to lower classes are less politically engaged because of their lack of status and lack of education. Instead, this is a prime example of how people who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds tend to be more disengaged with politics because they do not feel as though the policies put forward by political parties benefit them and that in fact they work against their favour. “Some groups in society have become less civically (and politically) active, and other groups have become more active,” (Sloam, et al. 2021) because of the representation that they receive from the different political parties.

This is a link to the Labour Party Manifesto that was put forward by Jeremy Corbyn: https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Real-Change-Labour-Manifesto-2019.pdf

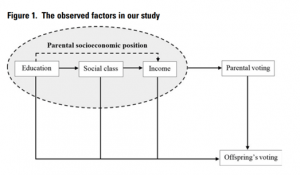

Evidently, Lahtinen et al (2019) reported that “current research considers parental education the most important socioeconomic factor in explaining the inter-generational persistence of political participation.” Young adults from upper socioeconomic backgrounds are usually exposed to a less filtered version of politics during their upbringing and tend to adapt to the same views as it is the norm to them. Unless they individually educate themselves on the different political parties and the policies that they offer, their views are subconsciously written by their parents. Thus, when it comes to political participation, the likelihood of an individual who was brought up exposed to political engagement being disengaged is low. However, intergenerational issues may begin to occur in some instances when individuals are exposed to differing views and political parties that go against the norm in which they have been brought up with. If young voters educate themselves on the world around them and develop their own views and values, then political participation may increase as they are more motivated for change.

Source from: Lahtinen, H. Erola, J. Wass, H. (2019). Sibling Similarities and the Importance of Parental Socioeconomic Position in Electoral Participation. In: Social Forces.

Young adults who have been socialised into participating and taking advantage of the democratic system in which they have been brought up in are more likely to politically engage in voting. However, I strongly disagree that this is based off of the socioeconomic status that you have and more so on your willingness to engage in politics and to educate yourself on the different political parties and their policies. It is up to us as individuals to learn about and participate in politics in order to either maintain or bring about new policies that benefit and appeal to us. No matter what your socioeconomic background may be, you are always delivered the opportunity to educate yourself on matters that are important to you and therefore be as politically engaged as you can be in order to see the change in the society you live in.

“Be the change that you wish to see in the world”- Mahatma Gandhi.

Bibliography:

Sloam, J. Kisby, B. Henn, M. et al. (2021). Voice, equality and education: the role of higher education in defining the political participation of young Europeans. In: Comparative European Politics.

Hoskins, B. Janmaat, J, G. (2016). Educational Trajectories and inequalities of political engagement among adolescents in England. In: Social Science Research.

Castillo, J, C. Miranda, D. Bonhomme, M. et al. (2015). Mitigating the political participation gap from the school: the roles of civic knowledge and classroom climate. In: Journal of Youth Studies.

Lahtinen, H. Erola, J. Wass, H. (2019). Sibling Similarities and the Importance of Parental Socioeconomic Position in Electoral Participation. In: Social Forces.